Great Housing Crash

|

Saving Communities

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

Where Will You Stand in the Great Housing Crash?A severe crash is inevitable, but some places will be hit much harder than others.by Dan Sullivan, director, Saving Communities February 2, 2008 (10 Seconds with Buster Keaton) Real estate prices must plummet. The value of any land you hold will fall, but how much it falls depends on the tax policies of your national, state, and local governments, as well as the zoning, demographics and indebtedness of your neighborhood. Essentially, places that have moved away from real estate taxes, particularly on land, have the least affordable housing and the heaviest debts. These places will suffer the greatest drop in values. Other factors, like dependence on the automobile, will also affect real estate prices. Lessons from Pittsburgh in the Great DepressionIt should be no surprise that the US city with the greatest drop in land prices during the Great Depression was Detroit, which was dependent on its volatile automotive industry. It is far more surprising, however, that Pittsburgh, which supplied much of the steel for automotive and other hard-hit industries, was able to sustain its land values remarkably well. Pittsburgh's land prices even fell less than those in Washington, DC, where the "business" of the New Deal was booming.

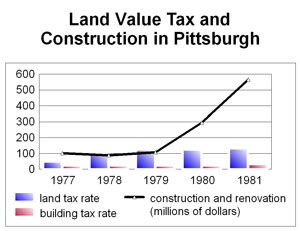

Why didn't Pittsburgh go bust like so many other cities? In terms of its industrial base and population growth, Pittsburgh had been booming. By the onset of the Great Depression, it was the seventh largest city in the United States. The rest of the country had changed its tax policies in ways that encouraged land speculation. Before 1910, over half the total tax burden in the United States had been coming from the land portion of the real estate tax. But with the introduction of federal income tax and increases in other state and federal taxes, the tax burden shifted off of speculators and onto productive investors. The result of this tax change and of loose-credit monetary policies was an orgy of land and stock speculation. Much of the stock speculation was indirect land speculation, with investors gambling on corporations that were in turn buying up land, natural resources, broadcast licenses and other privileges. Land prices more than tripled in many American cities between 1913 and 1925. In contrast, Pittsburgh had modified its real estate tax in 1913, gradually shifting its tax burden off of homes and improvements and onto the value of land. By 1925, the tax rate on land values was twice the rate on improvement values, and over 80% of Pittsburgh's total tax revenue was coming from land. During that time, land prices in Pittsburgh went up only 20%, despite tremendous economic growth and construction in that city. Real estate interests complained that the tax had made Pittsburgh's land undesirable, but those same interests were spared the subsequent collapse. History repeats itselfIn 1978, California put itself in the vanguard of the anti-property-tax movement by passing Proposition 13, which froze assessments, limited property tax rates to 1% of assessed value, and made it extremely difficult for local communities to increase property tax rates even within those constraints. Rampant land speculation followed. Foreign interests acquired as much California land in the 18 months following passage of Proposition 13 as they had accumulated during the entire history of that state. A construction boom was overshadowed by a much larger real estate price boom, until California had the most unaffordable housing in the United States. Although Proposition 13 was supposed to make home ownership easier, California now has the most unaffordable housing in the United States. In 2005, the median price of a house or condo was more than twelve times as high as the median annual household income in such California cities as Berkeley, Costa Mesa, Downey, Fullerton, Glendale, Los Angeles, and San Francisco. Even in parched, dusty Bakersfield, the median house price was more than 5.8 times as high as the median income. Compare that to Pittsburgh, one of the most affordable cities in the United States, where the 2005 median house price was only 2.4 times as high as the median income. [see Affordability Ranking, 243 US Cities.] California is now 49th in the percentage of housing units that are owner-occupied. Moreover, 79% of California's owner-occupied units are mortgaged, and, where property values have fallen, mortgaged balances often exceed those values. California has also had the most mortgage foreclosures and bankruptcies of savings & loan institutions since Proposition 13. Some Californians had even taken 50-year mortgages with no payment on principal for the first five years. As real estate prices fell, people walked away from $500,000 mortgages on homes that had fallen in value from $700,000 to $400,000. Sanity in PittsburghAt the end of 1978, Pittsburgh went in the opposite direction from California, doubling its tax rate on land values only. The following year, Pittsburgh raised the land value tax again, to over 2 1/2 times its pre-1978 rate, and in 1980, land tax went to over 2 2/3 the 1978 rate. Pittsburgh's land prices remained stable while construction levels soared. Fortune Magazine noted that Construction in 1980 leaped 212% above the 1977-78 average, reflecting groundbreaking for a new crop of office skyscrapers that is giving the city its so-called second renaissance (the first came in the 1950s with the redevelopment of the Golden Triangle). The adoption in 1980 of three-year tax exemptions on all new buildings

Once again, while the rest of the country saw real estate prices boom while the economy flagged, Pittsburgh's real estate prices remained stable while its construction boomed. And, once again, the worst price booms were in states that had moved away from real estate taxes. During the collapse of Savings & Loan associations, the only S&L that went bankrupt from the Pittsburgh area had been making loans in California. Unaffordable housing invites collapseAs California housing prices collapse and banks try to unload houses on which they will have foreclosed, it will become even more difficult for an ordinary California home seller to get anything like the price he had expected. California's business market will also weaken as businesses will discover that they can save on labor costs as well as on commercial rents by moving to places like Pittsburgh. After all, employees who enjoy lower rents and house prices can live better on smaller salaries. California is not the only state that overpriced itself by curtailing its property tax, and Pittsburgh is not the only city that kept itself affordable. For example, there has been a major migration from Massachusetts to New Hampshire in the wake of a 1980 Massachusetts referendum that tried to mimic California's Proposition 13. New Hampshire gets two thirds of its state and local revenues from property tax and has no general sales or income tax. It is not a good place for land speculators, but it is a great place for ordinary taxpayers. There are also 18 smaller cities in Pennsylvania that have adopted shifts to land value tax. They also enjoyed construction surges after making the shifts, and they also have very reasonable land prices. One can locate in any of these cities without being gouged by land speculators or tax collectors either. How did we ever forget?The lessons of the Great Depression were so severe that people vowed to never let anything like it ever happen again. For decades, banks made a point to only consider the value of improvements as collateral; parents told their children about the evils of speculation; "Never pay more than one year's income for a house," was still the prevailing conventional wisdom as late as the 1960s; and the Shakespearean line, "Neither a borrower nor a lender be," was accorded the reverence of profound truth. So how did we forget these lessons? The short answer is that we had no choice; our monetary system was designed to collapse unless we as a people suppressed what we had learned and put ourselves hopelessly into debt. The problem is that a growing economy needs a growing money supply, and, almost all new money in the United States is loaned into circulation. If we don't keep borrowing more and more, the system collapses. Sooner or later, however, we reach a point where we not only can't borrow any more but can't pay the interest on what we have already borrowed. That's where we are today. Hiding from the truthThe news that housing prices would inevitably collapse came a long time ago, but the American people and their leaders refused to listen. As far back as 1960, House & Home, the trade journal of the residential housing industry dedicated an entire issue to the subject of spiralling land prices, with such statements as, "FHA is deeply concerned over the way land prices are shooting up. The average land cost component in our valuations has climbed from $761 in 1946 to $2,362 in 1959." -- Julian Zimmerman, Federal Housing Administration commissioner "Steepest inflation of all has been the price inflation in land, but nobody is doing anything to stop it and we have no land policy designed to bring land into the market when it is needed. The result has been a largely fictitious shortage of land for housing that has pushed prices far above today's values and is almost sure to end in a bust." -- statement of economists and housing industry leaders of the House & Home Round Table on Inflation Today's fancy land prices can be kept high only as long as the illusion of scarcity can be preserved, as long as each buyer thinks the land he pays too much for today would cost more ScapegoatingAfter almost half a century of ignoring these warnings we can't deny the inevitable any longer, but we still blame every cause but the real cause. "Irresponsible lenders," is a convenient scapegoat, but more and more lending became necessary to delay the collapse until even "irresponsible" lending had to be winked at. The horrendous Iraq War is also an easy target, especially now that the war is so unpopular. Yet that war delayed the crash as well, even though it made us all poorer in the long run. Even our dependency on foreign oil, which will lead to real problems for communities designed around the automobile, is not the cause of the crash itself. The true causeThe true cause of real estate crashes is the interplay between land speculation and our debt-money system. People who have no reason to hold real estate other than to cash in on rising prices squeeze out home buyers and productive entrepreneurs. The home buyers and entrepreneurs can only compete by borrowing. That's where debt-money comes in. Banks have been allowed to create money out of nothing and lend it to us. The only limit is set by the Federal Reserve, and that limit has been continually increased to keep one step ahead of the crash. Because policy wonks at the Federal Reserve kept letting debts get bigger and bigger, real estate prices kept getting higher and higher. Everyone speculatesIn the broadest sense, speculation just means looking ahead, and almost anyone who is not living hand-to-mouth looks ahead to some degree. However, poorer people cannot afford to pay extra now for a home that they expect to grow in value. The better off a person is, the more he looks to the future. Although moderately successful professionals usually pay more to live in neighborhoods where they expect prices to rise, they rarely buy more real estate than they are going to use or rent out for others to use. Idle speculation, which creates artificial shortages of land and drives up prices, is a game for the unusually wealthy. The who, why and where of land speculationTrue speculators are basically people who aren't looking for an immediate return on their money as much as a long-term gain. They buy land when the long-term gain, after taxes, looks more promising than the long-term gain from a productive investment. If there is a rentable building on the land they buy, they will continue collecting rent and performing minimal maintenance. However, as their purpose is to sell the property someday, those with really deep pockets avoid making major improvements that a potential buyer might not want. Also, they do not want to spend money on improvements that could be spent buying more land. Most speculators buy when land prices are going up, causing them to go up even faster, and sell when prices are going down, causing them to go down even faster. The shrewdest buy before land prices start going up and sell before they start going down, but doing so requires other, less shrewd speculators to buy what they sell. As a local phenomenon, the economic effect is referred to as "gentrification" where prices are driven up by speculation and as "blight" where they are driven down. On a broader level, it is referred to as inflation and depression. However, even broad depressions do not impact all areas evenly. Wherever land speculation had been most rampant, depressions will be most severe. Where speculators pounceAs noted above, idle speculators look for the greatest gains after taxes. That means that they look for land that is not only headed up in value, but is also lightly taxed. Land near a new airport, highway interchange or other major project is a great prize for speculators, but it's an even greater prize if it's in a state that curtailed its property taxes, such as California, Massachusetts, or Florida. In those states, they can not only buy land in the path of progress, but can hold that land far longer, and at far less expense, than land that is near similar projects in states that rely on real estate taxes. In cities like Pittsburgh and states like New Hampshire, the out-of-pocket cost of real estate taxes discourages speculators from holding as much land or holding it for as long. Freezing under duressOne of the things that turns a real estate crash into a full-blown depression is the refusal of land owners to accept reality and sell at a loss. They try to wait for the economy to turn around and bring back high prices, but the economy cannot turn around until land becomes available at affordable prices. Often the full-time speculators have already unloaded their property on smaller, heavily mortgaged landowners who cannot recover what they had borrowed by selling. Still, as long as the sellers or landlords demand a higher price than what potential buyers or tenants are willing to pay, the economic outlook will continue to deteriorate. What to do nowAs an individual, you are well advised to minimize your real estate holdings. Sell if you can, because taking a small loss now is better than taking a huge loss in a few years, even if it means paying rent in the meantime. If you can afford to relocate, central US states tend to be less overpriced than southern and coastal states. Small cities and compact towns are less overpriced than big cities and their sprawling suburbs. Within those parameters, consider places that rely most heavily on property taxes, and consider the Pennsylvania cities that tax land values separately. Also, high-density locations will be able to provide decent public transportation when oil shortages destroy automobile-based communities, and looser zoning laws will allow the return of neighborhood businesses. The trendiest neighborhoods within a community are the worst deals at this point, even where real estate has been heavily taxed. Stable, blue-collar neighborhoods with a high percentage of unmortgaged, owner-occupied houses are very good. Neighborhoods with a high percentage of home owners from racial minorities also tend to be better priced because prejudice and past redlining practices have deflected inflationary pressures away from those neighborhoods. Good local policiesKeep assessments up-to-date. If a location is gaining value, it is doing well and able to pay its share. The locations that need help are the ones where prices are dropping, and good assessing helps by making the tax drop where the price has dropped. A small, abrupt drop in real estate prices is better than a big, slow decline. Local officials should light a fire under speculators, but also make it as easy as possible for them to sell and for productive investors to buy. If your community has a land value tax option, it should shift other taxes to land value tax. The more precarious the local economy is, the faster it should do so. If you do not have a land value tax option, property tax is the next best alternative. Start by abolishing any deed transfer taxes and building permit fees. If you have vacant land and a shortage of housing, replace the building portion of the property tax with land value tax. If you have unoccupied business properties, replace any business taxes with land tax. If you have unoccupied residences, replace gross receipts taxes and wage taxes. If the state will allow you to make per capita grants to people over 65, you can soften the blow to retirees. However, there is no justice in granting special breaks to elderly home owners at the expense of renters, or granting larger breaks to those who live in more valuable homes. Loosen or abolish zoning restrictions that prevent higher density construction. In a falling real estate market, people are going to locate where they can do as much as possible on as little land as possible. Allowing single-family home owners to subdivide large homes or to take in boarders will also help them stave off foreclosure. Allowing people to set up home-based or neighborhood businesses will also help. Don't create local debts to stimulate development, as there is a danger of monetary deflation, where debts will become terribly difficult to pay off. In making spending decisions, consider what an expenditure will do for land values, and think in terms of immediate returns. For example, bus service in some neighborhoods pays for itself many times over because people in those neighborhoods will pay more to live where they can work and shop. In other neighborhoods, bus service makes very little difference. You can best cut government spending by getting rid of economic development authorities, but keep up the general services that both employ people and maintain land values. When government gets overly involved in developing real estate, real estate owners get overly involved in government. It's better to remove obstacles than make deals or create artificial incentives. Good state policiesStop using sales and income taxes to fund local services that could be paid for from real estate taxes. Allow local jurisdictions to tax land values separately from improvements and to grant per capita rebates to people over 65. Allow each county or municipality to do its own assessing, but have a well-funded state oversight operation that investigates assessment accuracy, publishes the results, and allows property owners to cite those results in appealing their assessments. Abolish "clean and green" exemptions, agricultural exemptions and other interferences that attract land speculators and corporate agribusiness. Family farms actually do better in states that tax farmland heavily, because they are more land-efficient than their corporate competitors. See Gaffney, "Rising Inequality and Falling Property Tax Rates" Good national policiesNational governments can change their monetary systems to prevent housing collapses from expanding into full-blown depressions, but they won't. Banking interests and conservative politicians have brainwashed people into opposing the very thing that needs to be done, while liberals avoid antagonizing banks. The right way to expand the money supply is through deficit spending. Money that is spent into circulation continues to circulate with no strings attached. This is much better than lending money into circulation and making the public forever indebted to the lenders. While deficit spending is increased, deficit lending can be curtailed by increasing fractional reserve requirements. Under normal circumstances, the proper goal would be to balance increased spending with decreased lending to produce little or no inflation. In the current situation, however, moderate inflation might be necessary to avoid a major collapse. Deficit spending does not mean increased spending. Government could decrease its spending and run a deficit by decreasing its taxes even more. As it does so it should liquidate its government debts and help state and local jurisdictions liquidate theirs. Without government bonds to buy, affluent investors will invest in productive enterprises instead. Meanwhile, banks will be hungry for deposits so they can meet their increasing reserve requirements. National governments should curtail aid to state and local governments, as such aid tends to replace taxes on real estate with taxes on productivity. Alternative investment solutionsLand owners should find ways to put their land to good use and encourage local governments to make other land owners do the same. Even if it means a loss in the short run, it is the only thing that can prevent a much greater loss in the long run. The only things ordinary citizens should do, for themselves as well as the country, are take up no more land than they need, and give preference to places that tax land the most and tax production and exchange the least. Interests with large parcels of land they are unable to sell should consider creating intentional communities where land rent is continually reassessed, and where half of the land rent is used to provide amenities and rebate taxes that fall on community members. Such a project is particularly attractive to people who want to move forward but are stymied by high land prices that are likely to drop. Also, state and local governments are prohibited from creating alternative currencies, but consortia of major landlords are free to issue transferrable rent credits that function as money. As bank credit constricts and money becomes scarce, these rent credits can circulate locally and keep the local economy strong. This in turn enhances land values and profits the consortium. Local solutions firstWe don't see national governments taking effective steps until there is broad consensus on what those steps should be. Even with a general consensus, national governments are, by their very nature, in closer communication with powerful interests than with ordinary citizens. Local governments are not only closer to the people but are in competition with one another. Thus we see local governments showing the way, and the first thing we ask from state and national governments is to remove obstacles and let those local governments solve their own problems. Good national solutions will probably be adopted first in small countries. Rough times aheadIt's going to be a very rough decade or two. Let us resolve, once again, to make it the last of its kind. This time, let's also resolve to understand why these things happen. Those who master the dynamics of land speculation and monetary policy will be able to act in their own best interests, the best interests of their community, and the best interests of the overall economy. It takes study and courage, but not self-sacrifice. |

New PagesNavigationWe Provide

How You Can Help

Our Constituents

Fundamental Principles

Derivative Issues

Blinding Misconceptions

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

Saving Communities | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||