|

Saving Communities

|

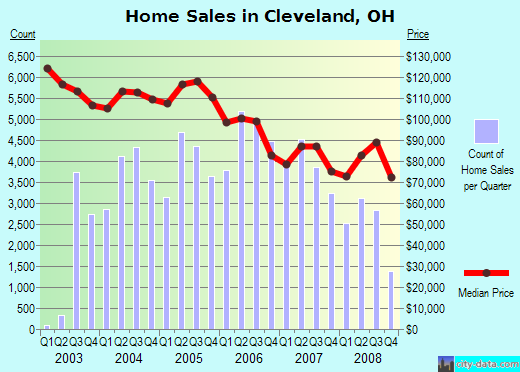

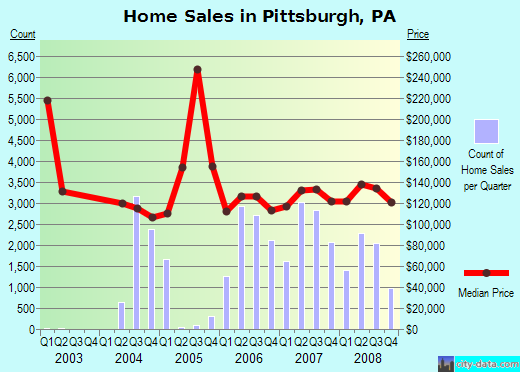

Why Cleveland Sinks and Pittsburgh SwimsPittsburgh saved by a forgotten reform that Cleveland championed.by Dan Sullivan, director, Saving CommunitiesCleveland is the poster child of the current depression, leading the nation in foreclosures for 2008, and Cleveland advocates are struggling to stem a complete collapse of its housing market. Meanwhile, Pittsburgh's foreclosure rates are low, home prices are climbing slightly, construction rates are increasing, and Pittsburgh housing advocates are warning against complacency. The culprit of the day is predatory lenders, who chose Cleveland as their feeding grounds, but the problem runs much deeper than that. Why wasn't Pittsburgh targeted by the same lenders? And why had Pittsburgh always rebounded during tough times that had hammered Cleveland throughout the twentieth century? During the Great Depression, Pittsburgh's land values fell a mere 11%, compared to 46% in Cleveland.[1] While Cleveland suffered through the post-war depression of the late 1940s, Pittsburgh enjoyed a major renaissance that was the subject of over two dozen national magazine articles.[2] After Pittsburgh lost its largest employer in 1979 to the demise of Big Steel, its resurged once again with another spectacular building boom. Apart from Pittsburgh's mysterious ability to rebound, it is strikingly similar to Cleveland. Both were industrial giants in their halcyon years. Cleveland was the nation's fourth largest city and Pittsburgh was the seventh. Cleveland was also the fourth largest corporate headquarters and Pittsburgh was third. More recently, both cities had undertaken similar economic development schemes and had made similar mistakes. Moreover, Cleveland started off the century with one of the greatest mayors in history, Tom Johnson.[3] Famed muckraker Lincoln Steffens, who described corrupt, smoky Pittsburgh as "Hell with the lid off, and politically the same with the lid left on,"[4] called Johnson "The best mayor of the best-governed city in America." So what happened to make corrupt, smoky Pittsburgh out-perform the best governed city in America? A clue can be found on Tom Johnson's statue in the Cleveland's public square. It shows Johnson holding the book, Progress and Poverty, by Henry George. George was the economic guru of the Progressive Era, and Johnson was George's biggest supporter, both financially and politically. Johnson pushed Ohio to let Cleveland adopt George's proposals. The full title of George's book was Progress and Poverty: An inquiry into the cause of industrial depressions and of increase of want with increase of wealth ...The Remedy. [emphasis added]. Called the economic bible of the Progressive Era, it blamed depressions on the over-taxation of business and labor and the under-taxation of land, making land speculation more profitable than productive enterprise. Its remedy was a "single tax" on the value of land to replace productivity taxes. Land value tax costs the owner of a vacant lot or a blighted property just as much as the owner of a well developed, well maintained property next door, yet it costs much more in rich neighborhoods where land is expensive than in poor neighborhoods where land is cheap, and costs the most in commercial centers where land is particularly dear. George's idea was for people holding unused or badly underused land to avoid the tax by letting go of the land. With land speculators out of the market, lower land prices attract development. The other side of George's proposal was to tax nothing else. If Cleveland had adopted this proposal, higher-income taxpayers and job-creating businesses would not have left the city to escape income and business taxes. Rather, they would have come to Cleveland from other cities that were taxing them. As land tax made speculators more willing to sell, the lack of building taxes and other productivity taxes would make home owners and job-creating businesses more eager to buy. However, Cleveland needed state permission to make this change, and the state government was not inclined to give anything to Johnson's Cleveland. It wasn't just that the Ohio legislature was Republican and Cleveland's mayor was a Democrat, or that Republicans were conservative and Democrats were progressive. To the contrary, many historians claim that the progressive movement had more Republicans than Democrats. After all, the Republican Party had formed out of several reform-minded minor parties less than half a century earlier, had abolished slavery, and was filled with people looking for other wrongs to right. Nor was the single-tax movement hostile to business. Johnson, a millionaire businessman himself, was joined in his reform efforts by banker Edward Doty, John C. Lincoln, founder and owner of Lincoln Electric, and other business leaders. Johnson's biggest problem promoting the reform was that state Republicans were under the control of his arch-rival, Mark Hanna. Hanna and Johnson owned competing streetcar franchises in Cleveland, and Johnson had successfully sued Hanna for the right to operate his streetcars on some of Hanna's rail lines. After Henry George had convinced Johnson that streetcar lines were natural monopolies that profited from gouging riders, Johnson charged much lower fares on his streetcars, to the embarrassment of Hanna's company. Finally, Johnson endeavored to have all Cleveland streetcar lines municipalized, and, when that failed, waged a protracted battle to force fares down to 3¢. While his battles with Hanna alienated state Republicans, some members of the Central Single-Tax Club of Cleveland had become insufferably militant, attacking "moderate" allies who proposed not to take all the rental value of land, but to take 90% and leave the rest to the landholders. Modern readers who recall the difficulties Barack Obama had with Rev. Jeremiah Wright can well imagine how these militants had hurt Johnson's efforts. Their rhetoric was too much even for the radical Henry George, who repudiated them as, "the gentlemen who since they have become so suddenly stricken with yearnings for the company of socialists and anarchists have come to look on [more moderate allies] as protectors of landlords, and schemers to degrade the movement into a "soulless, conscienceless fiscal reform." So, besides opposition from speculators, the usual opposition of one party to proposals from another, and the animosity of a notorious machine boss based on other political and business rivalries, Johnson had to cope with allies whose "more radical than thou" posture made people wary of his proposals and divided his base of support. The result was that the land value tax campaign failed in Cleveland, despite heroic efforts by Johnson and some of his successors. The story was different in Pittsburgh, however. First of all, Pittsburgh's government had no party rivalry with the state. Its progressives were mostly Republican progressives. The Republican Party's progressive roots were particularly strong in Pittsburgh. The Free Soil Democracy held its 1852 convention in Pittsburgh before merging into the Republican Party. Like the Free Soil Party that came before it, it called for reserving land to homesteaders instead of turning it over to speculators and monopolists. The Republican Party also held its first national convention in Pittsburgh, where it set up procedures for its first Presidential nominating convention. Pittsburgh was solidly Republican from 1856 to 1933. Second, Pittsburgh had just reformed itself politically, purging itself of "the most cold-blooded and vicious political ring that ever ruled an American city."[5] Although the purge had been spearheaded by a statewide independent party, the result was that machine Republicans were replaced by progressive reform Republicans. The Republican legislature had even abolished the corrupt city council, changing the city charter and replacing the large ward-based council with a smaller council elected at large. The state therefore had every reason to give the new city government the tools it needed. Third, Pittsburgh was being choked by a much worse property tax system. Wealthy estates within the city were classified as "agricultural" and "rural." Property taxes on ordinary businesses and residents were 50% higher than on "agricultural" land and twice as high as on "rural" land. Estate owners were able to hold out against Pittsburgh's economic growth by developing only small portions of their holdings. Land monopoly was so bad in Pittsburgh that it had second highest land prices in the nation, behind New York City.[6] Fourth, the Pittsburgh reform was backed by strong progressive elements the business community, including the Civic Commission, the Chamber of Commerce, the Allied Boards of Trade, and even the Real Estate Board (predecessor to the Association of Realtors). By winning this business support at the outset, reformers avoided association with strife between business and labor that had derailed reform in Cleveland. Finally, Pittsburgh's land tax advocates were able to avoid ideological divisiveness and focus on the practical benefits of the proposal. After Cleveland's reformers had bickered over ideological purity, Pittsburgh's reformers put forward a modest compromise that would not frighten the opposition. After abolishing the tax breaks for rural and agricultural land, and exempting industrial machinery from the property tax, Pittsburgh's reformers proposed a gradual shift from building tax to land tax over a 12 year period, ending with the tax rate on buildings that was half the land tax rate. It passed the state legislature without serious opposition, although landed interests launched a nearly successful repeal effort two years later. During the 1920s, while Cleveland and the rest of the nation were enjoying real estate price booms, Pittsburgh's land values barely rose, and it enjoyed a construction boom instead. This allowed Pittsburgh's land to hold most of its value through the Great Depression. [7] Pittsburgh still has several "temporary" taxes that were levied during the Great depression and World War II, but it was denied a "commuter" wage tax based on place of employment like Cleveland has. Because Pittsburgh is smaller than Cleveland (53 square miles vs. 77 square miles) more of Pittsburgh's regional legislators represent suburban interests, and those legislators successfully opposed giving Pittsburgh this option. Also, Philadelphia had been given a commuter tax option and discovered too late that the tax drove businesses out of the city even faster than the residential wage tax had been driving out residents. Today, several council members admit that the commuter wage tax is destructive, but that, politically, they cannot shift taxes off of non-voting suburbanites and onto voting Philadelphians. Pittsburgh faced huge deficits for the 1979 tax year. The prior mayor, a conservative populist, had cut property taxes by cutting maintenance. This left the new mayor with buildings, vehicles and roads in serious disrepair. Meanwhile, the city's largest employer, LTV Steel, was in the process of completely shutting down, laying off city residents and costing the city millions in lost wage taxes. To remedy the situation, the mayor called for major tax increases during three of his first full term. He proposed to put these increases on wage and business taxes. However, Pittsburgh's home-rule charter allowed it to shift further toward land value tax. Council president William Coyne showed that the wage tax cost typical home owners twice as much as a property tax and three times as much as a land value tax. City council put most or all of the increases on the land value tax all three times, twice overriding the mayor's veto. The real estate editor of Fortune wrote a major story on how these increases spurred Pittsburgh's second surge in construction. Pittsburgh raised its tax rate on land from 4.95% to 9.85% of assessed valuation in 1979, while leaving the rate on buildings at 2.475%. New construction, measured by the dollar value of building permits issued, rose 14% as compared with the 1977-78 average. In 1980 the city widened the differential still more, to a tax rate of 12.55% on land vs. the 2.475% building rate, a ratio of 5.07 to 1. (With Allegheny County and school taxes added in, the final ratio was 2.99 to 1.) Construction in 1980 leaped 212% above the 1977-78 average, reflecting ground breaking for a new crop of office skyscrapers that is giving the city its so-called second renaissance (the first came in the 1950s with the redevelopment of the Golden Triangle). The adoption in 1980 of three-year tax exemptions on all new buildings -- but not the land -- also boosted construction. In 1981 construction peaked at nearly six times the 1977-78 rate. Some of the dozen new office towers that gone up in Pittsburgh would have been built with or without tax concessions; downtown office space had been growing scarce. But the widening differential between the taxes on buildings and land undoubtedly helped. It cut the annual bill for owners of some skyscrapers by more than $500,000 a year when compared with conventional 1:1-ratio taxation.[8] In 1984, Pittsburgh lowered the building tax .5 % and increased the land tax to make up the difference. In 1988, Pittsburgh cut the wage tax by 5/8% to stem the out-migration of working people, In 1989, it cut wage tax another 1/2%, increasing land tax. The out-migration slowed considerably. More importantly, Pittsburgh remained affordable during the housing bubble of the 1990s. Pittsburgh went back to conventional property tax in 2002, after an outside assessing firm hired by the county had butchered land assessments. Most home owners got substantial tax increases, and city council has been gutting the budget rather than raise a tax that falls so heavily on home owners. It is likely that, unless Pittsburgh straightens out its assessments and re-enacts the land value tax, the next real estate bubble will catch Pittsburgh as well. Meanwhile, perhaps Ohio will finally give Cleveland the options that Tom Johnson fought for 100 years ago, so Cleveland's city economy can go from worst to best for this century, just as Pittsburgh's had for the last century. Footnotes: [1] Williams, Percy, Pittsburgh's Graded Tax, its History and Experience. [3]Johnson was ranked second best mayor in American history in a poll of 140 political scientists and historians with expertise in urban issues. The American Mayor: The Best & the Worst Big-city Leaders? by Melvin G. Holli. [4]"Pittsburgh: A City Ashamed, McClure's, May 1903, p. 24 [5] George Swetnam, Bicentennial History of Pittsburgh and Allegheny County, Historical Record Association, Pittsburgh, Pa., 1956, Vol. 1. [6] Pittsburgh Civic Commission, Civic Bulletin, January, 1912; also An Act to Promote Pittsburgh's Progress, published by Pittsburgh Civic Commission in 1913. [7] Williams, Percy, Pittsburgh's Graded Tax, its history and experience, Appendix, Table 2 [8] "Higher Taxes that Promote Development," Fortune, August 8, 1983 |

New PagesNavigationWe Provide

How You Can Help

Our Constituents

Fundamental Principles

Derivative Issues

Blinding Misconceptions

|

Saving Communities | ||